Letter from London

Does architecture really make a difference to the way we live and work? To listen to some critics, you would think not, writes Paul Finch.

Especially given the well-rehearsed complaints about housing shortages, traffic congestion and strategic infrastructure failures. (In respect of the latter, it is little surprise that Mayor Sadiq Khan says the strengthened and re-opened Hammersmith Bridge will not be available to ordinary motorists – another vindictive attack on those who live on the south side of the Thames.)

Hammersmith Bridge

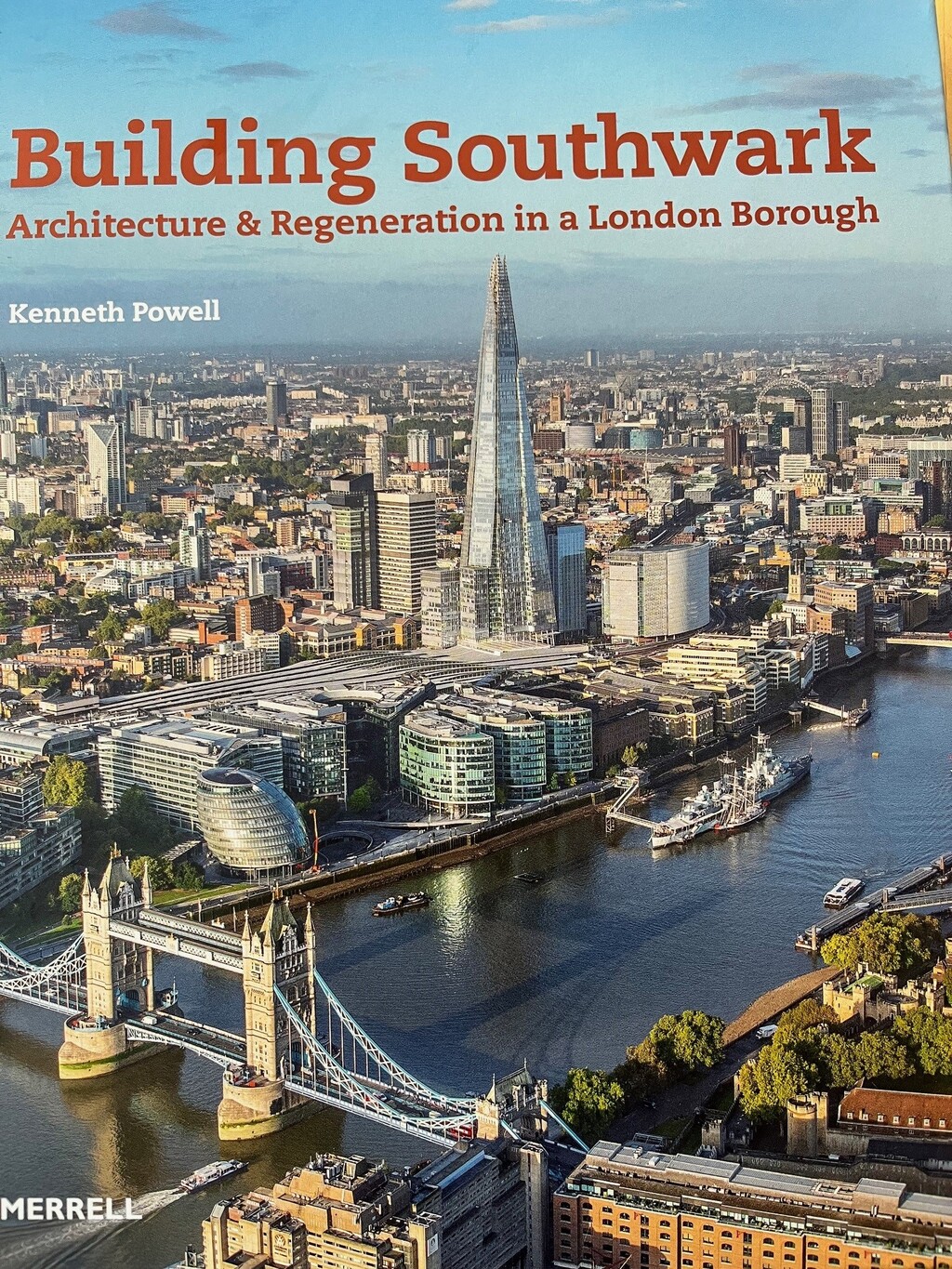

So as a form of relief, and a bonus for those of an optimistic disposition, you could turn to a wide-ranging survey of contemporary architecture, assembled by the veteran critic Kenneth Powell. Building Southwark: Architecture & Regeneration in a London Borough (Merrell) is a reminder about the benefits of good design, and how important the role of a planning authority will be in allowing or encouraging it to happen.

Divided into six sensible sections, starting with Culture and Leisure, the book (produced with support from the council and various developers who have done significant work in the borough) includes all the big-hitting projects one would expect to see. Forget about the abject failure of Hammersmith Bridge – what about the triumph of London Bridge Station, the greatest London work by Grimshaw?

London Bridge Station by Grimshaw (Photo: Paul Raftery)

It is difficult to do justice to this or other major projects like the Shard, in the context of a double-page spread, but the well-chosen photographs and drawings do their best; oddly, small projects tend to come over better than architecture of genuine complexity, even if confined to one page, but this is really a publication for the interested general reader.

What that reader will find is evidence of an extraordinary range of architectural approaches rather than the municipal house style that characterised the mass-scale housing developments in the borough during the 1960s and 70s. Kenneth Powell, in a useful introduction, reminds us of the comment made in The Buildings of England about the council’s Aylesbury Estate: ‘An exploration can only be recommended for those who enjoy being stunned by the impersonal megalomaniac creations of the mid-20th century.’

Whatever the noble social aspirations of the council in the 50 years following World War II, the outcomes were, it must be admitted, disastrous both socially and architecturally. Southwark, one of the biggest owners and developers of public housing in Britain, has learned from the mistakes of its predecessors, judging by the variety of pleasing housing architecture on display in this volume.

The architectural monoculture of yesteryear has vanished, to be replaced by a variety of approaches related to scale, height and geographical location within the borough. Tall buildings (up to 50 storeys) are allowed/encouraged in the Southwark Local Plan at Blackfriars/London Bridge, Elephant & Castle and Canada Water. Towers by PLP, Allies & Morrison, KPF and Foster & Partners are individually distinctive, but their height inevitably dilutes their difference, though Simpson Haugh’s One Blackfriars remains a terrific icon. Elsewhere, dense low-rise development has spawned greater difference, most notably in the work of Peter Barber, whose expressionist exercises in brick contrast with the distinctive work of AHMM, and the quieter work of Witherford Watson Mann, or HTA.

One Blackfriars by SimpsonHaugh Architects (Photo: Hufton + Crow)

Welcome variety is also evident in the sections covering Mixed Use, Education and Landscape – what a pleasure to see gardens and parks of different scale in this most urban of boroughs.

While this survey is about 21st century architecture in the borough, there is no denying the importance of the 1960s in creating the context for what has happened in Southwark since it became a super-borough in 1965, following the Conservative reorganization of London government. Bermondsey and Camberwell’s town halls vanished, as did Walworth’s – the strange death of localism as distinctive ‘villages’ across London lost their identities.

Those old town halls, mainly 19th or early 20th century, were focal points for settlements comprising parishes which had medieval roots. The smashing up of old London sounded go-ahead at the time (dumping Middlesex County Council; creating an entirely bogus relationship between ‘Havering’ in the East to Hounslow in the West), but in retrospect was it wise?

The old London County Council, a model of municipal efficiency run from the magnificent County Hall (paid for by public subscription), was replaced by the grander Greater London Council, but it didn’t last long. Mrs Thatcher flogged off County Hall to the highest bidder (a Japanese developer), having comprehensively dismantled the GLC itself.

That madness was reversed under Tony Blair with the creation of the Greater London Authority, but of course County Hall was gone forever. Now London is run from an interesting but low-key building in an inconvenient East London location, having been moved by Mayor Khan from the GLA’s first home in the Foster & Partners customised offices by Tower Bridge.

City Hall by Foster + Partners

A sorry tale of architectural decline, foreshadowed by the loss of all those old town halls, and local communities they represented. Southwark, at least, has worked hard to establish a new 21st century identity, making the most of the capital’s considerable architectural talent.

Founder Partner