Coping with the supermarket juggernaut

Some years ago, driving at speed in the outside lane of a motorway, I suddenly became aware of a large lorry close behind, writes Paul Hyett.

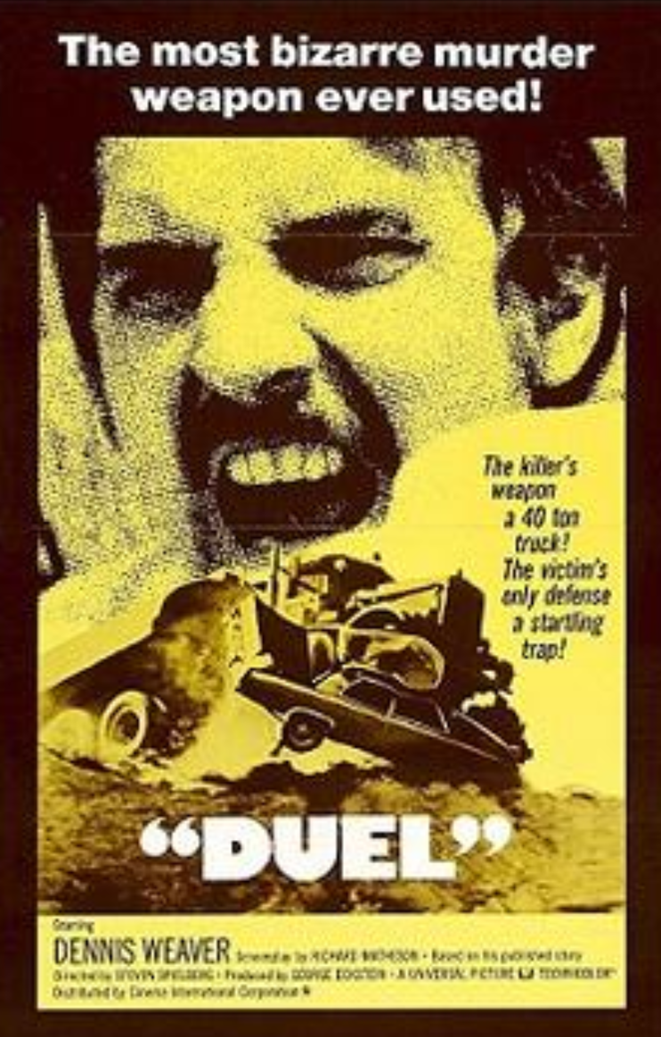

The driver was incredibly threatening, constantly flashing his headlights, and occasionally sounding the horn in truly menacing fashion. I was reminded of that great Steven Spielberg film ‘Duel’, in which a travelling salesman (played by Dennis Weaver) finds himself chased and terrorised by the mostly unseen, yet evidently psychotic, driver of an articulated truck.

Original screen poster for the film

Extremely irritated, I pressed my car’s hazard warning button, but in a raw display of aggression, the lorry driver accelerated, narrowing the gap between our vehicles to what seemed to be inches. I pulled over to let him and the danger pass – and was so angry that I reported the harassment to the driver’s employers. The company never responded.

This experience has certain parallels with my feelings about the Tesco supermarket chain and its architecture, the real subject of this column: a giant bearing down unstoppably on anything which gets in its way. And it has lorries too...

My antipathy towards the company goes back to the 1960s when Tesco opened a supermarket in my home town, Hereford. Now a McDonald’s, the building was sufficiently alien in the streetscape to impact on my sensibilities, even as a 15-year-old. The image below reveals the upper façade, where windows, roofscape and materials served only to compromise the scale and character of the streetscape.

Tesco’s Hereford store, now a McDonald’s

A decade later, Tesco built a much larger store offering that most invaluable of all facilities, an underground car park, just inside Hereford’s ancient city wall on the opposite side of town. As the image below shows, though somewhat kitsch, this was, architecturally, an altogether better effort, albeit assisted by a combination of the historic city wall that it abutted, and the trees that in summer at least, serve to conceal it.

Tesco’s replacement store

These efforts did little, however, to alleviate a wider damage caused. As in similar situations elsewhere, the new store shifted the centre of gravity of the city, simultaneously undermining the economic viability of its main shopping streets and draining them of their lifeblood: people.

In the decades that have intervened, Tesco and latterly competitors such as Morrisons and Asda, have wreaked havoc on the towns and cities across our country, not just in terms of their architecture, but also their brutal strangling of the local economies, and indeed the way of life of many of our citizens.

Such changes seem all the more shocking as we see their effect on even the smallest of towns. Take, for example, the Cefn-Bychan area in Wrexham, north Wales. For reasons of no doubt economic sense, Tesco recently decided that this tiny settlement of around a hundred or so houses, was worthy of its attentions. Sensing the potential for more than its simplest offering (a Tesco ‘Express Store’) the company sourced a site of sufficient size to take one of its superstores. This was achieved through persuading the local football club to relocate to a relatively remote location, in return for financial assistance with new facilities.

Cefn-Bychan’s new Tesco

To be fair, the architecture is far from the worst. But it all comes at great cost: in one fell swoop, the giant corporate has destroyed the town’s local traders and only a couple of independent hairdressers and a charity shop seem to have survived. Otherwise, all the other once vibrant shop windows are now empty, replaced by a megastore that, in its entirety, is introspective: for Tesco shop windows are a thing of the past.

The story is all too familiar in terms of the undermining of a small town’s retail and commercial life. The reason is, of course, that big stores sell just about everything from food to medicines and from hardware to stationery. This not only kills the local baker, butcher and fishmonger – it marks the end of the chemist and other locally owned and run shops and services. Even Cefn-Bychan’s few cafes suffer as – yes, you got it – Tesco offers refreshments and ‘a place to meet and talk’ as well.

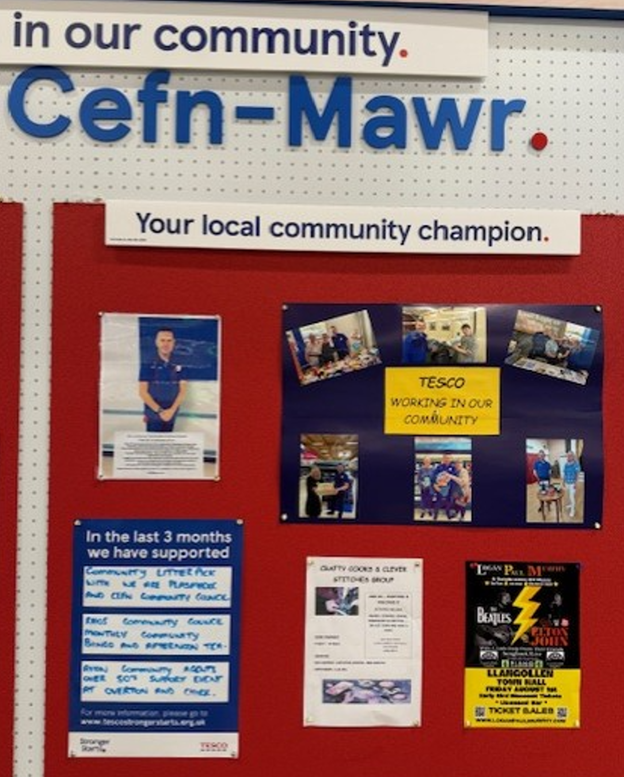

Laudably, as its in-store ‘community notice board’ proclaims, ‘Tesco Cefn-Bychan’ also supports many local initiatives including, over the last three months, Community Litter Pick, Community Bingo and Afternoon Tea and Overton and Chirk Over ‘50s Support Event in which it partners with various community organizations. The store even has its own ‘Community Champion’, an employee whose responsibilities include helping with community programme initiatives such as food donations and grants; coordinating donations for community events such as school sports days; and providing guidance for charities and community groups.

The community champion’s notice board

These stores have collectively monopolised our custom and ruthlessly disconnected us from those who formerly supplied our needs, and from those who serve us (when was the last time you spoke to the check-out sales person – if one still exists in your increasingly automated store?).

That said, there can be no going back – there will be no collective decision to re-engage the milkman, and through that process, re-connect with our local dairy farm, and familiarise ourselves once more with the baker, the banker and the dozens of other retailers and suppliers that, just in my lifetime, were once familiar figures to us all.

The architect Cedric Price used to talk of the three stages in the evolution of towns, likening them first to a poached egg where townsfolk once lived within the city walls at night and went out to the fields by day to work; then to fried eggs where people lived in the suburbs and journeyed in to town to work in commerce or manufacturing; and finally to scrambled eggs where those definitions became blurred beyond recognition.

There are no easy answers to the rebuilding of towns with the characteristics all too sadly lost, but a possible new financial model could see the town centre (once more) as first and foremost a residential and cultural hub – that is cultural in the widest sense of that term. Thus the centre would move beyond being principally a trading base (big retailers operating on the outskirts would do all that), and instead re-purpose itself to what it can do so well: that is, provide a safe and convenient place for living, and for cultural and social exchange.

In delivering such a strategy, government would ultimately have to curb housebuilders’ incessant hunger for cheap land around existing towns as sites for their low-density, all too often low-grade housing. Instead, as has been achieved in places like Nantwich, a beautiful and vibrant 15,000-person town in Cheshire, the focus would be upon the constant reinforcing of the centre through conversions of existing surplus buildings for residential and cultural use, and the sensitive development of higher density new-build housing on awkward but often larger infill sites.

Such strategies are not only essential to the survival of our towns as vibrant centres, but they offer huge benefits because they put homes where people most want them: that is, within existing and well supported infrastructure. What better way to make inroads into our alleged homes crisis.

With 1.5 million homes in demand here in the UK, some serious and joined up architectural and political thinking is much-needed.

Founder Partner